Retsina is a part of Greece’s heritage. I am using the term heritage, as it refers to “something inherited from the past”. Wine with added resin has been made in Greece for about 2500 years. That is a long time!

Retsina is a part of Greece’s heritage. I am using the term heritage, as it refers to “something inherited from the past”. Wine with added resin has been made in Greece for about 2500 years. That is a long time!

Despite its long history, it took all but 10 years for Retsina to become a global synonym for Greek wine: During the 1960s, commercial and bottled Retsina became available. This coincided with the tourist boom, when a large number of travellers began to discover Greece. Suddenly, the name Retsina shot to fame. The large producers quickly built upon this momentum by exporting enormous quantities of the new darling.

The excitement did not last long: While consumers became more sophisticated in the following years, a lot of plain and even bad Retsina was sold unabated as cheap, mass market wine. The boom ebbed away, yet the taint has remained to this day. This is slowly beginning to change. There are a number of Greek winemakers who seek to build upon old traditions and craft a sophisticated and modern style of Retsina. These are pioneers in their own right and they are a paragon of just how dynamic the Greek wine industry has become over the last years.

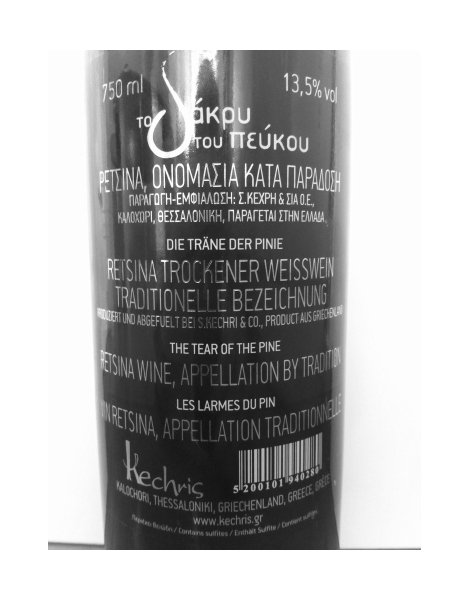

The Kechris winery belongs to those visionaries. Their top offering is a Retsina called “The tear of the pine”. Retsina is usually made from the Savatiano variety and to a lesser extent from Roditis. Kechris went for the noble Assyrtiko grape instead. The fermentation takes place in new oak barrels and the wine spends some time on its lees. The current 2010 vintage is a must-try. It does not come cheap, retailing around 13 Euros. But what a stunning wine this is: The aromas are dominated by fresh lime; the resin is obvious, but not overpowering at all. There are also nuances of citrus peel, lavender and vanilla. It is beautifully balanced on the palate and the acidity is really put to work here. It is medium bodied, and full with citrus and ginger notes – an explosion for the senses. The mid-palate is particularly rewarding and the finish lingers on for quite some time. This is a very fine wine indeed.

Please keep in mind that Retsina is foremost a wine to be enjoyed with food. Greek dishes are a natural choice, apart from a number of mezedes; it pairs perfectly with a number of grilled fishes like red mullet or sardines. It is also real winner with spicy and exotic dishes; try it with Thai or Indian cuisine.

Side fact: “The tear of the pine” was selected by Konstantinos Lazarakis MW for the “Discovering Greek wine” programme which is run by Aegean airlines. It was offered during the last quarter to its business class passengers. What a great way to raise awareness of how extraordinary great Retsina can be.

Nerd fact: Retsina belongs to the category “Wines of traditional appellation”. Resin must be between 0.15 and 1% of the final product, the minimum acidity is 4.5 g/l, and the alcohol level must be between 10 and 13.5%.

Kechris, Gaia, Kontoyiannis & some other producers in Attica are revamping retsina and thank God for that as it has been synonymous in the past with cheap “rotgut” wine and you would often hear descriptions such as “rocket fuel” or “paint stripper” from tourists who had ventured to try some whilst over here. Like ouzo, retsina is not a quaffer and will only make sense when tried wth food – especially some oily or fried foods. When faced with some “wine killer” foods such as curries or skordalia, a well made retsina takes these in its stride whereas most other wines would struggle. Context is what counts. For instance dry sherries never made much sense to me until I tried them with salty almonds, olives or other “difficult” foods.

Retsina was produced and consumed all over Greece, but if it has to be linked to a specific place of origin, this is the Attica plateau, and more specifically the Mesogeia subregion, hence its varietal composition of mainly savvatiano, a largely undervalued grape according to many. Fortunately, there is still a number of Mesogeia based producers who stubbornly focus on this grape for their modern day retsinas (Vassiliou, Papagiannakos etc.). Assyrtico on the other hand, is certainly Greece’s noblest white, but I have some objections on whether it has to be used as a pass-partout in order to modernize and improve any kind of traditional Greek wine. Kechris’s effort is admirable of course, but I admire even more those who try to modernize the product remaining loyal to its traditional components.